After 3 years of anticipation, it was with great enthusiasm that more than 30 dairy producers from several regions of Quebec, as well as from Eastern Ontario, participated in visits to dairy farms and tourist attractions, from March 20 to 27.

This trip, organized by Uniag Cooperative, had been planned in March 2020, a few days after the announcement of a pandemic.

After arriving in Calgary, the group was able to marvel at the beautiful scenery of the Rocky Mountains, enjoying the bright sunshine.

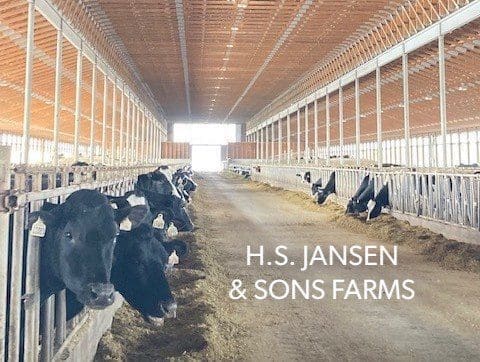

Jansen Dairy was the first farm visited, located in the Okanagan Valley it has the distinction of having relocated to this region 18 years ago. As the price of land became too important to continue the expansion in their region of origin (the Fraser Valley, where an acre sold for twice as much as in the Kelowna Valley), this family business of Dutch origin was able to integrate the 3rd generation.

The 1,200 cow, 1,600 kg quota farm is currently the only one to use an approved milk truck scale in BC.

They use a geothermal system to cool the milk, while recovering the heat produced.

Milking is done in a 50 seat carousel, 3 times a day. They use a 5-mile underground pipe system to deliver liquid manure to their land, as well as an irrigation system that allows them to add 6 to 12 inches of water, depending on the soil structure, to get better crop yields.

The newly built nursery has a heated room for the newborns where they receive their first care.

A little further west, we arrived near Chilliwack, in the Fraser Valley region, where 70% of British Columbia’s milk is produced.

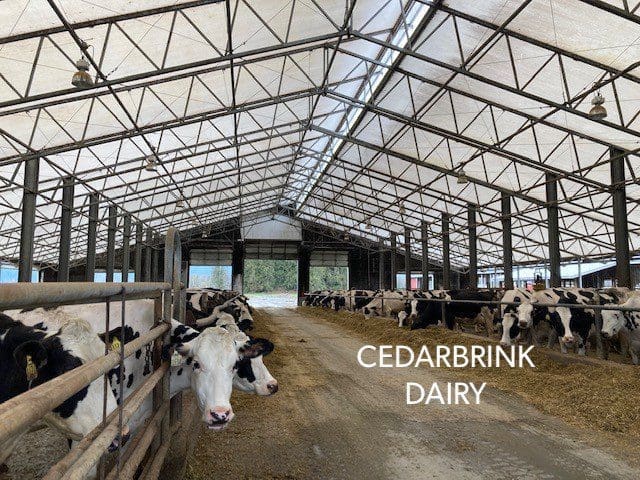

Cedarbrink Dairy is run primarily by Nigel Vandenbrink, 35 years old, 3rd generation from Holland. The farm has 800 cows, producing 1.45 kg of fat per day. The expansion has been quite rapid as the quota has increased by 400 kg in the last 3 years. Another site with 300 cows produces exclusively A2A2 milk. On a third site, located in Merritt, in a more arid climate, they raise their replacement animals in conjunction with another farm as well as fattening steers for slaughter.

To alleviate the enormous pressure on land prices, they have purchased 3000 acres 9 hours north of BC, producing their own grain (barley, wheat) and dry hay. It should be noted that in the Fraser region, the very rainy climate is not conducive to dry hay.

Like all the other farms visited, she includes whey permeate in the ration; the main source of protein is canola meal. And they use recycled sand in the stalls.

The land surrounding the main site produces 2 crops per year (winter wheat and rye grass, followed by corn silage).

The last barn built was a WeCover type. The next one will be of the same type, since the animals seem to appreciate the brightness and a cooler temperature in summer according to the owner.

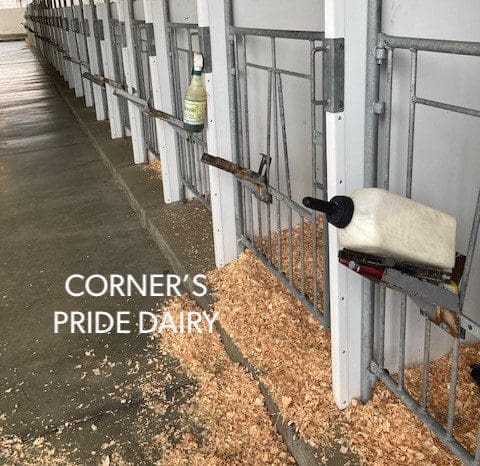

Close by, we visited Corner’s Pride Dairy, owned by a three-person corporation, with its 31 milking robots and 1,700 cows. The robotic shift dates to 2017, and the farm has two other sites for breeding. There are many protocols in place, including those affecting births.

Alleys are cleaned by a water flush system, as well as robot scrapers for some barns.

Currently, the production is 37 kg per cow at 4.6% fat with a single feed cubed in the robot. The average number of milkings is 2.7 per day. About 8% of the cows are pushed into the robots twice a day. Sorting for cows to be treated or inseminated is done in blocks of 13 hours.

Also in the Fraser Valley, George Dick, owner of Dicklands Farm, showed us his unusual biodigester facility: two 1 million gallon biodigesters (half from farm manure, half from food waste). A building of about 100 x 200 feet houses various rooms equipped with machines that can sort plastic from food waste, separate solid from liquid, dry residues, separate and clean water, and recover and purify hot air using various innovative techniques proven in Scandinavian countries.

The entire process will be in operation by June 2023, producing the equivalent of 4.5 million liters of natural gas, as well as 8.5 million liters of water and 4,000 tons of solid fertilizer in cubes.

George Dick is working to make his dairy farm low methane and carbon dioxide emissions in conjunction with government subsidies. Currently, the 300 lactating cows are milked by 5 robots and produce an average of 39 kg per day, at 4.9% fat and 3.4% protein.

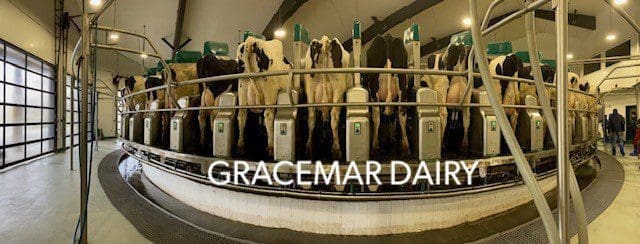

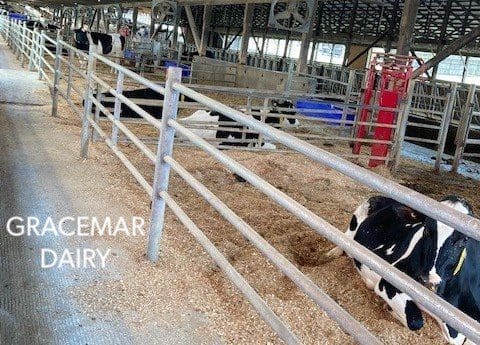

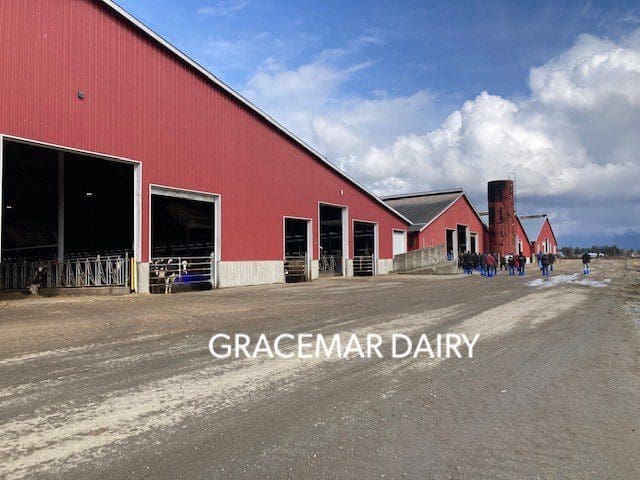

The 60-seat robotic carousel was definitely the focal point of the visit to Gracemar Dairy. The 1200 cows of this farm are milked 3 times a day while being divided into groups. This group consists of 375 cows milked in just one hour. One person supervises the milking, while another brings in the groups. The implementation of this type of milking robot was able to save huge costs on labor, thus allowing to keep a family dimension.

The other particularity of Gracemar Dairy is that they do not breed. All cows are inseminated with Angus bulls, and about 30 cows are purchased per month.

As on previous farms, the emphasis is on making the cows comfortable in preparation for calving, which allows them to produce 1.65 kg of fat per cow per day.

In the Fraser Valley, land is worth around $120,000 per acre. This is due to urbanization and competition with vegetable producers and blueberry growers. Nevertheless, Gracemar Dairy is planning to invest in land purchases, as they only own 300 acres and rent 700 acres at $1000/acre.

Finally, it was at Eco-Dairy farm, located in the middle of an urban area, that we ended our journey. This farm is first and foremost educational, since the city dwellers are explained all the facets of milk and meat production by visiting the various well-maintained barns.

It is also a research site where several trials are conducted, some in collaboration with the University of British Columbia. There is also an IVF site for donors of different breeds.

It was an instructive and constructive immersion in the dairy world of British Columbia, where the reality of the dairy industry is sometimes similar to ours, sometimes totally different.