The summer production dip returns year after year, despite changes in management, feed and genetics implemented to avoid it and adjust to the market. It’s the same scenario everywhere, whether in Quebec, Florida or Pennsylvania. Strategies exist to reduce the consequences.

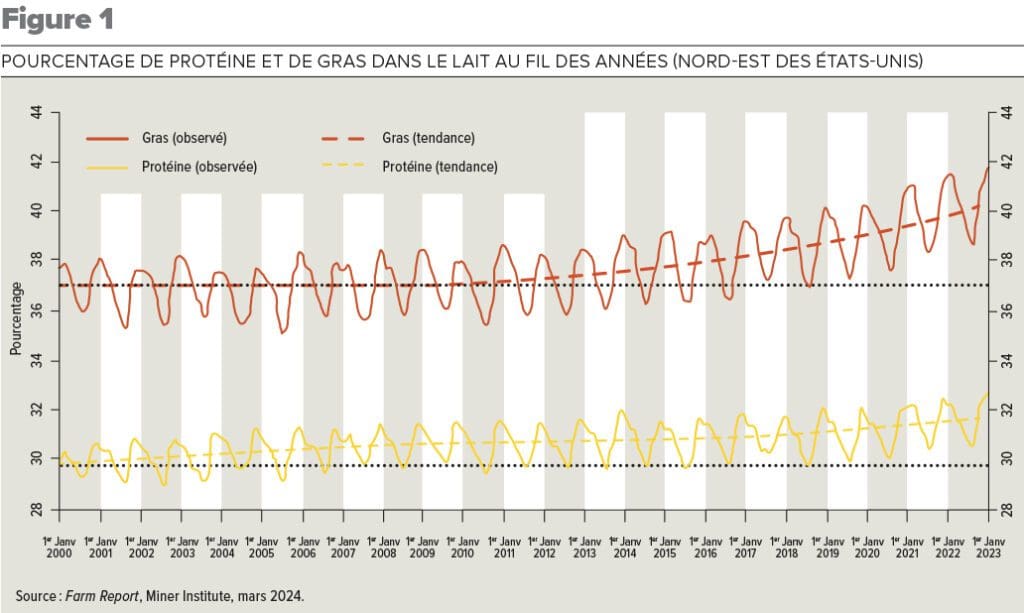

Some will say that the summer of 2023 lacked heat and sunshine, but the cow production cycle followed the same downward trend as usual. The Miner Institute’s March 2024 Farm Report illustrates very well that seasonal variation in milk production has existed for decades.

HEAT OR PHOTOPERIOD?

Research results conducted by the University of Pennsylvania suggest that there is a circannual production rhythm related to changes in photoperiod. The decrease in production during the summer is due not only to increased heat but also to this rhythm embedded in the cows’ metabolism.

Can we, on a herd basis, completely eliminate these production variations by reducing heat stress? Perhaps not, but one thing is certain: the strategies implemented to cool cows in the summer yield positive results in the short and long term. Let’s first look at the impact that an increase in cows’ body temperature can have.

HEAT STRESS AND PERFORMANCE

The first response of an animal’s metabolism to heat stress is a decrease in intake and productivity. The drop in production is greater than the drop in intake because some of the available energy is used to maintain body temperature.

The more milk a cow produces, the more its metabolism transforms nutrients and the more heat it generates. It is estimated that the critical temperature at which a cow will suffer from heat is 5 °C lower if it produces 45 kg compared to 35 kg of milk. The highest producers will therefore be the most affected by heat.

HEAT BALANCE AND BEHAVIOR

As we talk about energy balance, we also talk about “heat” balance. The cow produces, dissipates, and absorbs heat, but its net balance must remain at zero for its body temperature to remain stable.

To reduce its heat production, the cow:

- reduces its intake, particularly its fiber intake which generates a lot of heat when fermenting;

- prioritizes the oxidation of glucose rather than fats to produce cellular energy;

- reduces its activities, thus moves and walks less.

To increase its heat dissipation, the cow:

- increases its respiration rate to more than 60 breaths per minute;

- redirects its blood flow to the extremities to allow more evaporation through the skin;

- spends more time standing to promote more surface evaporation.

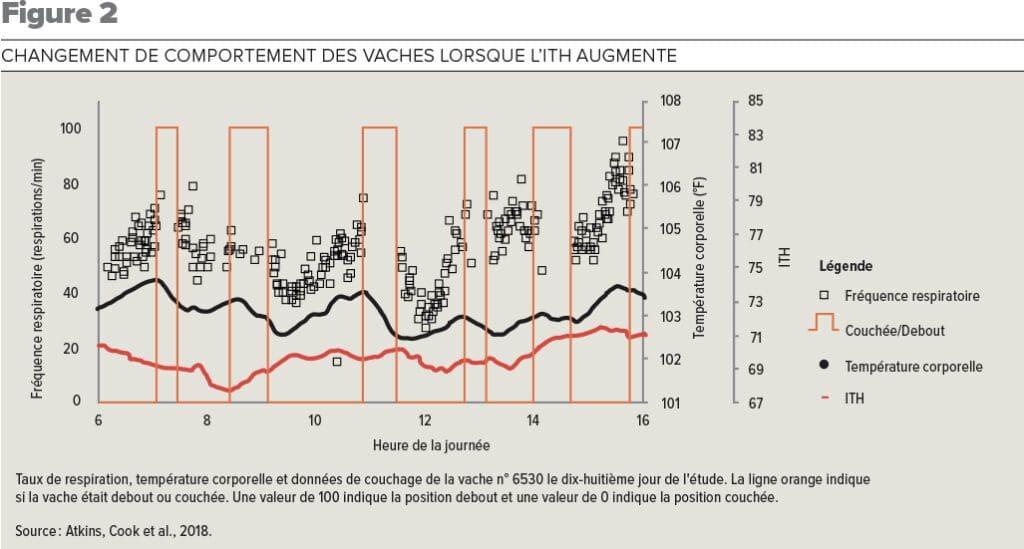

Figure 2 clearly illustrates the change in cows’ behavior. When the combined temperature and humidity index (THI) increases, the body temperature rises (black curve), the respiration rate exceeds 60 breaths/min (black squares). To dissipate this heat, the cow stands up (high orange line); when its temperature drops, it lies down (low orange line).

Heat stress can reduce lying time by 30%. Since rumination is more efficient when lying down, this change in the time budget harms feeding efficiency due to poorer rumen health, increased energy needs to stay standing and dissipate heat, and lower blood flow to the mammary gland when standing rather than lying down.

HEAT STRESS AND REPRODUCTION

As cows reduce their activities, it becomes more difficult to detect estrus since they will be much less demonstrative. Therefore, one must keep a keen eye. Detection protocols facilitate the identification of estrus, but the negative impact of increased body temperature on breeding success will not be eliminated because the cows’ hormonal system is also altered by heat.

Changes in the secretion of hormones such as progesterone, estrogen, and luteinizing hormone (LH) have been observed. Follicular development and embryo survival are also compromised. Short-term or long-term heat stress during the period around insemination is likely to negatively affect the conception rate (CR).

Whether it is a one-day stress or longer, the risk exists. The CR can drop by more than 20%. Since the cow has a 21-day cycle, we understand that the impact may take a few months to manifest, which explains why reproductive parameters may take time to return to normal.

HEAT STRESS AND LAMENESS

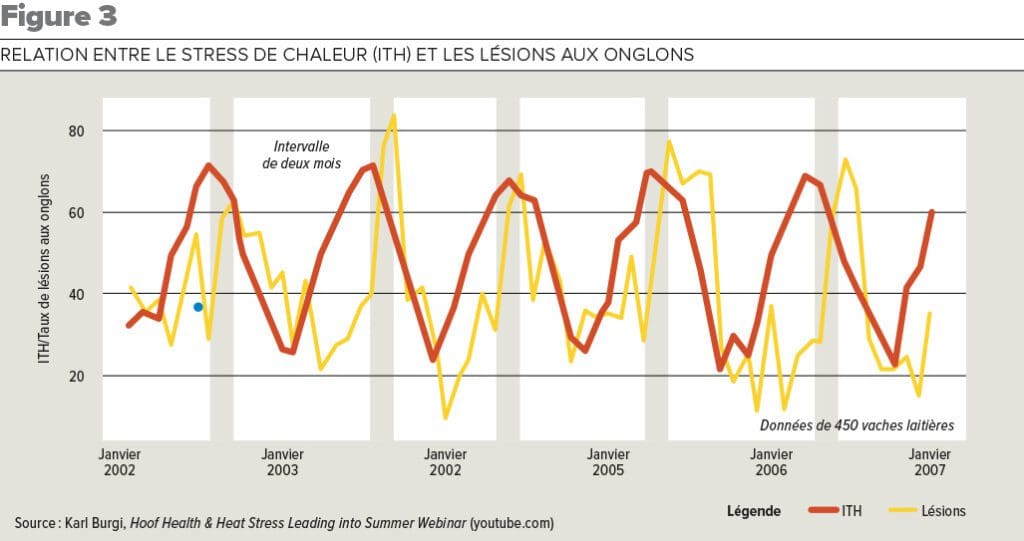

The fact that cows spend more time standing puts additional pressure on their hooves, which can cause inflammations that often manifest two months later. Figure 3, taken from a presentation by hoof health expert Karl Burgi, highlights the two-month delay between temperature increases (orange line) and the increase in lesions (yellow line).

Since heat stimulates the growth of microorganisms in the bedding, the hygiene of the stalls should not be neglected during heat waves to avoid causing more mastitis and metritis in addition to lameness linked to the change in behavior. It is not uncommon to see increases in somatic cell counts in the summer. Lame cows walk less, which results in fewer visits to the feeder, fewer visits to the milking robot, fewer signs of heat, etc.

VENTILATION AND BEHAVIOR

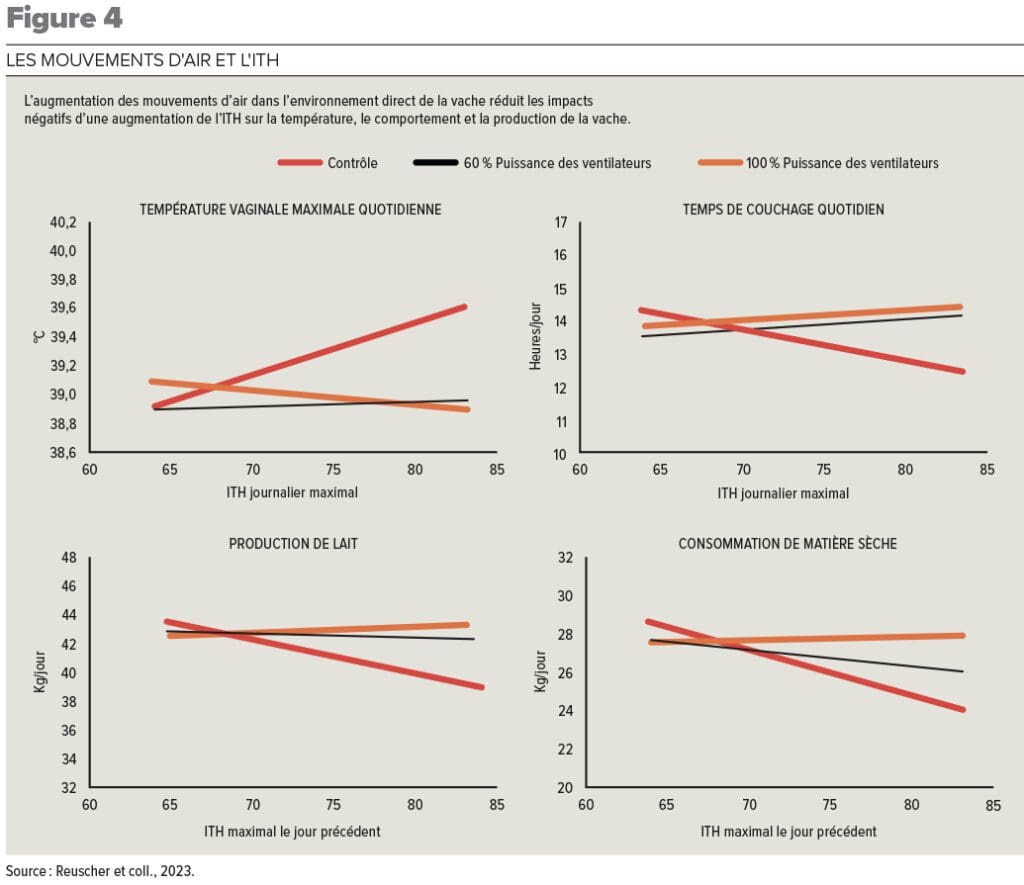

The use of fans to increase air movement around the cows is an effective way to help them maintain their body temperature and restore a certain normality in their time budget, as demonstrated by the results of a study conducted by the University of Wisconsin in 2023. The impact of three ventilation regimes was compared in an environment where the THI was around 75, thus above the threshold of 68 considered problematic.

The cows were exposed to air movements of 0.4 m/s (control), 1.7 m/s (60% of the fans’ capacity), or 2.4 m/s (100% of the fans’ capacity) measured at 0.5 m above the lying area. Increased air circulation helped reduce the cows’ body temperature and restore lying time, resulting in increased voluntary dry matter intake and milk production despite heat stress (Figure 4).

WHAT TO DO?

We now understand that heat stress affects the metabolism and behavior of our dairy cows. Discuss the Oasis program with your consultant. Since body temperature is at the heart of the observed changes, the first objective should be to implement ventilation systems that can cool the cows and ensure that air movements are sufficient around the cows (including dry cows), whether in the stalls, at the feeder, in the milking parlor waiting area, or in the robot waiting area.

Header photo by Patrick Nadeau

Article seen in Le Coopérateur

Texte from Annick Delaquis Annick Delaquis